Hi everyone! In this article we will talk about memoization, an optimization technique that can help make heavy computation processes more efficient.

We will start by talking about what memoization is and when it's best to implement it. Later on we will give practical examples for JavaScript and React.

Table of Contents

- What is memoization

- How does memoization work

- JavaScript memoization example

- React memoization example

- Roundup

What is Memoization?

In programming, memoization is an optimization technique that makes applications more efficient and hence faster. It does this by storing computation results in cache, and retrieving that same information from the cache the next time it's needed instead of computing it again.

In simpler words, it consists of storing in cache the output of a function, and making the function check if each required computation is in the cache before computing it.

A cache is simply a temporary data store that holds data so that future requests for that data can be served faster.

Memoization is a simple but powerful trick that can help speed up our code, especially when dealing with repetitive and heavy computing functions.

How Does Memoization Work?

The concept of memoization in JavaScript relies on two concepts:

- Closures: The combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function was declared. You can read more about them here and here.

- Higher Order Functions: Functions that operate on other functions, either by taking them as arguments or by returning them. You can read more about them here.

JavaScript Memoization Example

To clarify this mumbo jumbo, we'll use the classic example of the Fibonacci sequence.

The Fibonacci sequence is a set of numbers that starts with a one or a zero, followed by a one, and proceeds based on the rule that each number (called a Fibonacci number) is equal to the sum of the preceding two numbers.

It looks like this:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, …Let's say we need to write a function that returns the nth element in the Fibonacci sequence. Knowing that each element is the sum of the previous two, a recursive solution could be the following:

const fib = n => {

if (n <= 1) return 1

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2)

}If you're not familiar with recursion, it's simply the concept of a function that calls itself, with some sort of base case to avoid an infinite loop (in our case if (n <= 1)).

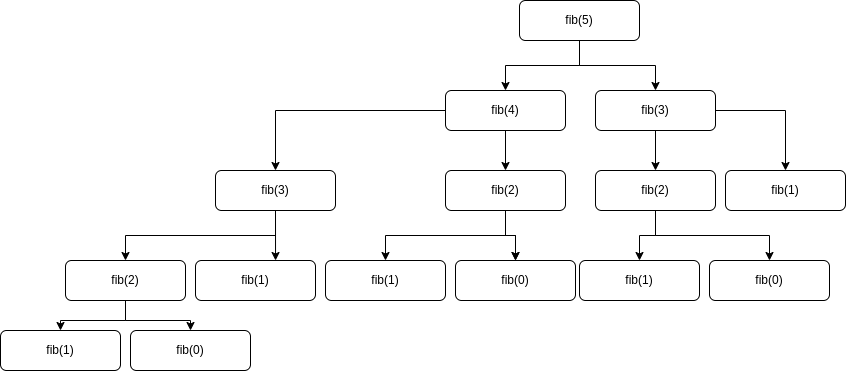

If we call our function like fib(5), behind the scenes our function would execute like this:

See that we're executing fib(0), fib(1), fib(2) and fib(3) multiple times. Well, that's exactly the kind of problem memoization helps to solve.

With memoization, there's no need to recalculate the same values once and again – we just store each computation and return the same value when required again.

Implementing memoization, our function would look like this:

const fib = (n, memo) => {

memo = memo || {}

if (memo[n]) return memo[n]

if (n <= 1) return 1

return memo[n] = fib(n-1, memo) + fib(n-2, memo)

}What we're doing first is checking if we've received the memo object as parameter. If we didn't, we set it to be an empty object:

memo = memo || {}Then, we check if memo contains the value we're receiving as a param within its keys. If it does, we return that. Here's where the magic happens. No need for more recursion once we have our value stored in memo. =)

if (memo[n]) return memo[n]If we don't have the value in memo yet, we call fib again, but now passing memo as parameter, so the functions we're calling will share the same memoized values we have in the "original" function. Notice that we add the final result to the cache before returning it.

return memo[n] = fib(n-1, memo) + fib(n-2, memo)And that's it! With two lines of code we've implemented memoization and significantly improved the performance of our function!

React Memoization Example

In React, we can optimize our application by avoiding unnecessary component re-render using memoization.

As I mentioned too in this other article about managing state in React, components re-render because of two things: a change in state or a change in props. This is precisely the information we can "cache" to avoid unnecessary re-renders.

But before we can jump to the code, let's introduce some important concepts.

Pure Components

React supports either class or functional components. A functional component is a plain JavaScript function that returns JSX, and a class component is a JavaScript class that extends React.Component and returns JSX inside a render method.

And what is a pure component then? Well, based on the concept of purity in functional programming paradigms, a function is said to be pure if:

- Its return value is only determined by its input values

- Its return value is always the same for the same input values

In the same way, a React component is considered pure if it renders the same output for the same state and props.

A functional pure component could look like this:

// Pure component

export default function PureComponent({name, lastName}) {

return (

<div>My name is {name} {lastName}</div>

)

}See that we pass two props, and the component renders those two props. If the props are the same the render will always be the same.

On the other side, say for example we add a random number to each prop before rendering. Then the output might be different even if the props remain the same, so this would be an impure component.

// Impure component

export default function ImpurePureComponent({name, lastName}) {

return (

<div>My "impure" name is {name + Math.random()} {lastName + Math.random()}</div>

)

}Same examples with class components would be:

// Pure component

class PureComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>My "name is {this.props.name} {this.props.lastName}</div>

)

}

}

export default PureComponent// Impure component

class ImpurePureComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>My "impure" name is {this.props.name + Math.random()} {this.props.lastName + Math.random()}</div>

)

}

}

export default ImpurePureComponentPureComponent Class

For class pure components, to implement memoization React provides the PureComponent base class.

Class components that extend the React.PureComponent class have some performance improvements and render optimizations. This is because React implements the shouldComponentUpdate() method for them with a shallow comparison for props and state.

Let's see it in an example. Here we have a class component that is a counter, with buttons to change that counter adding or subtracting numbers. We also have a child component to which we're passing a prop name which is a string.

import React from "react"

import Child from "./child"

class Counter extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = { count: 0 }

}

handleIncrement = () => { this.setState(prevState => {

return { count: prevState.count - 1 };

})

}

handleDecrement = () => { this.setState(prevState => {

return { count: prevState.count + 1 };

})

}

render() {

console.log("Parent render")

return (

<div className="App">

<button onClick={this.handleIncrement}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={this.handleDecrement}>Decrement</button>

<h2>{this.state.count}</h2>

<Child name={"Skinny Jack"} />

</div>

)

}

}

export default Counter

The child component is a pure component that just renders the received prop.

import React from "react"

class Child extends React.Component {

render() {

console.log("Skinny Jack")

return (

<h2>{this.props.name}</h2>

)

}

}

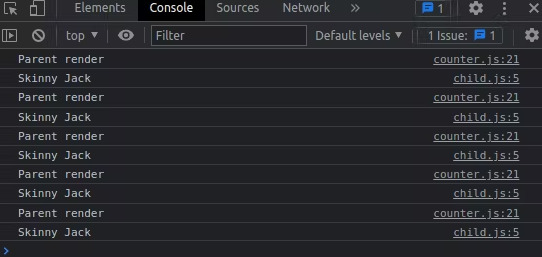

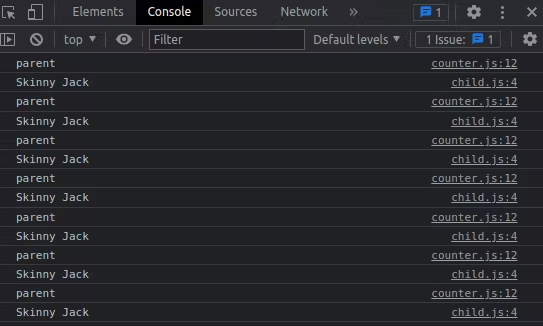

export default ChildNotice that we've added console.logs to both components so that we've get console messages each time they render. And speaking of that, guess what happens when we press the increment or decrement buttons? Our console will look like this:

The child component is re-rendering even if it's always receiving the same prop.

To implement memoization and optimize this situation, we need to extend the React.PureComponent class in our child component, like this:

import React from "react"

class Child extends React.PureComponent {

render() {

console.log("Skinny Jack")

return (

<h2>{this.props.name}</h2>

)

}

}

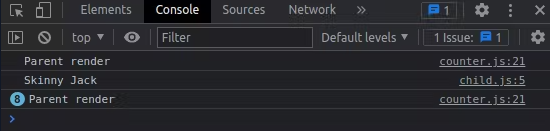

export default ChildAfter that, if we press the increment or decrement button, our console will look like this:

Just the initial rendering of the child component and no unnecessary re-renders when the prop hasn't changed. Piece of cake. ;)

With this we've covered class components, but in functional components we can't extend the React.PureComponent class. Instead, React offers one HOC and two hooks to deal with memoization.

Memo Higher Order Component

If we transform our previous example to functional components we would get the following:

import { useState } from 'react'

import Child from "./child"

export default function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const handleIncrement = () => setCount(count+1)

const handleDecrement = () => setCount(count-1)

return (

<div className="App">

{console.log('parent')}

<button onClick={() => handleIncrement()}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={() => handleDecrement()}>Decrement</button>

<h2>{count}</h2>

<Child name={"Skinny Jack"} />

</div>

)

}import React from 'react'

export default function Child({name}) {

console.log("Skinny Jack")

return (

<div>{name}</div>

)

}This would provoke the same problem as before, were the Child component re-rendered unnecessarily. To solve it, we can wrap our child component in the memo higher order component, like following:

import React from 'react'

export default React.memo(function Child({name}) {

console.log("Skinny Jack")

return (

<div>{name}</div>

)

})A higher order component or HOC is similar to a higher order function in javascript. Higher order functions are functions that take other functions as arguments OR return other functions. React HOCs take a component as a prop, and manipulate it to some end without actually changing the component itself. You can think of this like wrapper components.

In this case, memo does a similar job to PureComponent, avoiding unnecessary re-renders of the components it wraps.

When to Use the useCallback Hook

An important thing to mention is that memo doesn't work if the prop being passed to the component is a function. Let's refactor our example to see this:

import { useState } from 'react'

import Child from "./child"

export default function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const handleIncrement = () => setCount(count+1)

const handleDecrement = () => setCount(count-1)

return (

<div className="App">

{console.log('parent')}

<button onClick={() => handleIncrement()}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={() => handleDecrement()}>Decrement</button>

<h2>{count}</h2>

<Child name={console.log('Really Skinny Jack')} />

</div>

)

}import React from 'react'

export default React.memo(function Child({name}) {

console.log("Skinny Jack")

return (

<>

{name()}

<div>Really Skinny Jack</div>

</>

)

})Now our prop is a function that always logs the same string, and our console will look again like this:

This is because in reality a new function is being created on every parent component re-render. So if a new function is being created, that means we have a new prop and that means our child component should re-render as well.

To deal with this problem, react provides the useCallback hook. We can implement it in the following way:

import { useState, useCallback } from 'react'

import Child from "./child"

export default function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const handleIncrement = () => setCount(count+1)

const handleDecrement = () => setCount(count-1)

return (

<div className="App">

{console.log('parent')}

<button onClick={() => handleIncrement()}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={() => handleDecrement()}>Decrement</button>

<h2>{count}</h2>

<Child name={ useCallback(() => {console.log('Really Skinny Jack')}, []) } />

</div>

)

}

And that solves the problem of unnecessary child re-rendering.

What useCallback does is to hold on to the value of the function despite the parent component re-rendering, so the child prop will remain the same as long as the function value remains the same as well.

To use it, we just need to wrap the useCallback hook around the function we're declaring. In the array present in the hook, we can declare variables that would trigger the change of the function value when the variable changes too (exactly the same way useEffect works).

const testingTheTest = useCallback(() => {

console.log("Tested");

}, [a, b, c]);When to Use the useMemo Hook

useMemo is a hook very similar to useCallback, but instead caching a function, useMemo will cache the return value of a function.

In this example, useMemo will cache the number 2.

const num = 1

const answer = useMemo(() => num + 1, [num])

While useCallback will cache () => num + 1.

const num = 1

const answer = useMemo(() => num + 1, [num])

You can use useMemo in a very similar way to the memo HOC. The difference is that useMemo is a hook with an array of dependences, and memo is a HOC that accepts as parameter an optional function that uses props to conditionally update the component.

Moreover, useMemo caches a value returned between renders, while memo caches a whole react component between renders.

When to Memoize

Memoization in React is a good tool to have in our belts, but it's not something you should use everywhere. These tools are useful for dealing with functions or tasks that require heavy computation.

We have to be aware that in the background all three of these solutions add overhead to our code, too. So if the re-render is caused by tasks that are not computationally heavy, it may be better to solve it in other way or leave it alone.

I recommend this article by Kent C. Dodds for more info about this topic.

Round up

That's it, everyone! As always, I hope you enjoyed the article and learned something new. If you want, you can also follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter.

Cheers and see you in the next one! =D