JavaScript is a multi-paradigm language and can be written following different programming paradigms. A programming paradigm is essentially a bunch of rules that you follow when writing code.

These paradigms exist because they solve problems that programmers face, and they have their own rules and instructions to help you write better code.

Each paradigm helps you solve a specific problem. So it's helpful to have an overview of each of them. We'll cover functional programming here.

At the end of this article, there are some resources you can use to go further if you enjoyed this introduction.

There's also a GitHub glossary that'll help you decode some of the jargon that functional programming uses.

Lastly, you'll find a place to get your hands dirty coding with practical examples and a GitHub repo full of resources you can use to learn more. So let's dive in.

Declarative vs Imperative Programming Paradigms

One example of these paradigms I talked about at the beginning is object-orientated programming. Another is functional programming.

So what exactly is functional programming?

Functional programming is a sub-paradigm of the Declarative programming paradigm, with its own rules to follow when writing code.

What is the declarative programming paradigm?

If you're coding in a language that follows the declarative paradigm, you write code that specifies what you want to do, without saying how.

A super simple example of this is either SQL or HTML:

SELECT * FROM customers<div></div>In the above code examples, you aren't implementing the SELECT or how to render a div. You are just telling the computer what to do, without the how.

From this paradigm, there are sub-paradigms such as Functional programming. More on that below.

What is the imperative programming paradigm?

If you're coding in a language that follows the imperative/procedural paradigm, you write code that tells how to do something.

For example, if you do something like below:

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

increment += arr[i];

}You are telling the computer exactly what to do. Iterate through the array called arr, and then increment each of the items in the array.

Declarative vs Imperative programming

You can write JavaScript in the Declarative paradigm or the Imperative paradigm. This is what people mean when they say it's a multi-paradigm language. It's just that functional code follows the Declarative paradigm.

If it helps you remember, an example of a declarative command would be to ask the computer to make you a cup of tea (I don't care how you do it, just bring me some tea).

Whilst imperatively, you would have to say:

- Go to the kitchen.

- If there is a kettle in the room, and it has enough water for a cup of tea, turn on the kettle.

- If there is a kettle in the room, and it doesn't have enough water for a cup of tea, fill the kettle with enough water for a cup of tea, then turn on the kettle.

- And so on

So what is Functional Programming?

So what does this mean for functional code?

Because it's a sub-paradigm from the Declarative paradigm, this affects the way you write functional code. It generally leads to less code, because JavaScript already has a lot of the in-built functions you commonly need. This is one reason people like functional code.

It also allows you to abstract away a lot (you don't have to understand in depth how something gets done), you just call a function that does it for you.

And what are the rules that lead to functional code?

Functional programming can be simply explained by following these 2 laws in your code:

- You architect your software out of pure, isolated functions

- You avoid mutability and side-effects

Let's dig into that.

1. Architect your software out of pure, isolated functions

Let's start at the beginning,

Functional code makes heavy use of a few things:

Pure functions

The same input always gives the same output (idempotence), and has no side effects.

An idempotent function, is one that, when you reapply the results to that function again, doesn't produce a different result.

/// Example of some Math.abs uses

Math.abs('-1'); // 1

Math.abs(-1); // 1

Math.abs(null); // 0

Math.abs(Math.abs(Math.abs('-1'))); // Still returns 1

Math.abs(Math.abs(Math.abs(Math.abs('-1')))); // Still returns 1Side effects are when your code interacts with (reads or writes to) external mutable state.

External mutable state is literally anything outside the function that would change the data in your program. Set a function? Set a Boolean on an object? Delete properties on an object? All changes to state outside your function.

function setAvailability(){

available = true;

}Isolated functions

There is no dependence on the state of the program, which includes global variables that are subject to change.

We will discuss this further, but anything that you need should be passed into the function as an argument. This makes your dependencies (things that the function needs to do its job) much clearer to see, and more discoverable.

Ok, so why do you do things this way?

I know this seems like lots of restrictions that make your code unnecessarily hard. But they aren't restrictions, they are guidelines that try to stop you from falling into patterns that commonly lead to bugs.

When you aren't changing your code execution, forking your code with if 's based on Boolean's state, being set by multiple places in your code, you make the code more predictable and it's easier to reason about what's happening.

When you follow the functional paradigm, you'll find that the execution order of your code doesn't matter as much.

This has quite a few benefits – one being, for example, that to replicate a bug you don't need to know exactly what each Boolean and Object's state was before you run your functions. As long as you have a call stack (you know what function is running/has run before you) it can replicate the bugs, and solve them more easily.

Reusability through Higher order functions

Functions that can be assigned to a variable, passed into another function, or returned from another function just like any other normal value, are called first class functions.

In JavaScript, all functions are first class functions. Functions that have a first class status allow us to create higher order functions.

A higher order function is a function that either take a function as an argument, returns a function, or both! You can use higher order functions to stop repeating yourself in your code.

Something like this:

// Here's a non-functional example

const ages = [12,32,32,53]

for (var i=0; i < ages.length; i++) {

finalAge += ages[i];

}

// Here's a functional example

const ages = [12,32,32,53]

const totalAge = ages.reduce( function(firstAge, secondAge){

return firstAge + secondAge;

})

The in-built JavaScript Array functions .map, .reduce, and .filter all accept a function. They are excellent examples of higher order functions, as they iterate over an array and call the function they received for each item in the array.

So you could do:

// Here's an example of each

const array = [1, 2, 3];

const mappedArray = array.map(function(element){

return element + 1;

});

// mappedArray is [2, 3, 4]

const reduced = array.reduce(function(firstElement, secondElement){

return firstElement + secondElement;

});

// reduced is 6

const filteredArray = array.filter(function(element){

return element !== 1;

});

// filteredArray is [2, 3]Passing the results of functions into other functions, or even passing the functions themselves, in is extremely common in functional code. I included this brief explanation because of how often it is used.

These functions are also often used because they don't change the underlying function (no state change) but operate on a copy of the array.

2. Avoid mutability and side-effects

The second rule is to avoid mutability – we touched on this briefly earlier, when we talked about limiting changes to external mutable state – and side effects.

But here we'll expand further. Basically, it boils down to this: don't change things! Once you've made it, it is immutable (unchanging over time).

var ages = [12,32,32,53]

ages[1] = 12; // no!

ages = []; // no!

ages.push("2") // no!If something has to change for your data structures, make changes to a copy.

const ages = [12,32,32,53]

const newAges = ages.map(function (age){

if (age == 12) { return 20; }

else { return age; }

})Can you see I made a copy with my necessary changes?

This element is repeated over and over again. Don't change state!

If we follow that rule, we will make heavy use of const so we know things wont change. But it has to go further than that. How about the below?

const changingObject = {

willChange: 10

}

changingObject.willChange = 10; // no!

delete obj.willChange // no!

The properties of changingObject should be locked down completely. const will only protect you from initializing over the variable.

const obj = Object.freeze({

cantChange: 'Locked' }) // The `freeze` function enforces immutability.

obj.cantChange = 0 // Doesn't change the obj!

delete obj.cantChange // Doesn't change the obj!

obj.addProp = "Gotcha!" // Doesn't change the obj!If we can't change the state of global variables, then we need to ensure:

- We declare function arguments – any computation inside a function depends only on the arguments, and not on any global object or variable.

- We don't alter a variable or object – create new variables and objects and return them if need be from a function.

Make your code referentially transparent

When you follow the rule of never changing state, your code becomes referentially transparent. That is, your function calls can be replaced with the values that they represent without affecting the result.

As a simple example of checking if your code is referentially transparent, look at the below code snippet:

const greetAuthor = function(){

return 'Hi Kealan'

}You should be able to just swap that function call with the string it returns, and have no problems.

Functional programming with referentially transparent expressions makes you start to think about your code differently if you're used to object orientation.

But why?

Because instead of objects and mutable state in your code, you start to have pure functions, with no state change. You understand very clearly what you are expecting your function to return (as it never changes, when normally it might return different data types depending on state outside the function).

It can help you understand the flow better, understand what a function is doing just by skimming it, and be more rigorous with each function's responsibilities to come up with better decoupled systems.

You can learn more about referential transparency here.

Don't iterate

Hopefully, if you've paid attention so far, you see we aren't changing state. So just to be clear for loops go out the window:

for(let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

total += arr[i];

}Because we are changing a variable's state there. Use the map higher order function instead.

More Features of Functional Programming

I hope at this point you have a good overview of what functional code is and isn't. But there's some final concepts used heavily in functional code that we have to cover.

In all the functional code I have read, these concepts and tools are used the most, and we have to cover them to get our foundational knowledge.

So here we go.

Recursion in Functional Programming

It's possible in JavaScript to call a function from the function itself.

So what we could always do:

function recurse(){

recurse();

}The problem with this is that it isn't useful. It will run eventually until it crashes your browser. But the idea of recursion is a function calling itself from its function body. So let's see a more useful example:

function recurse(start, end){

if (start == end) {

console.log(end)

return;

} else {

console.log(start)

return recurse(start+1, end)

}

}

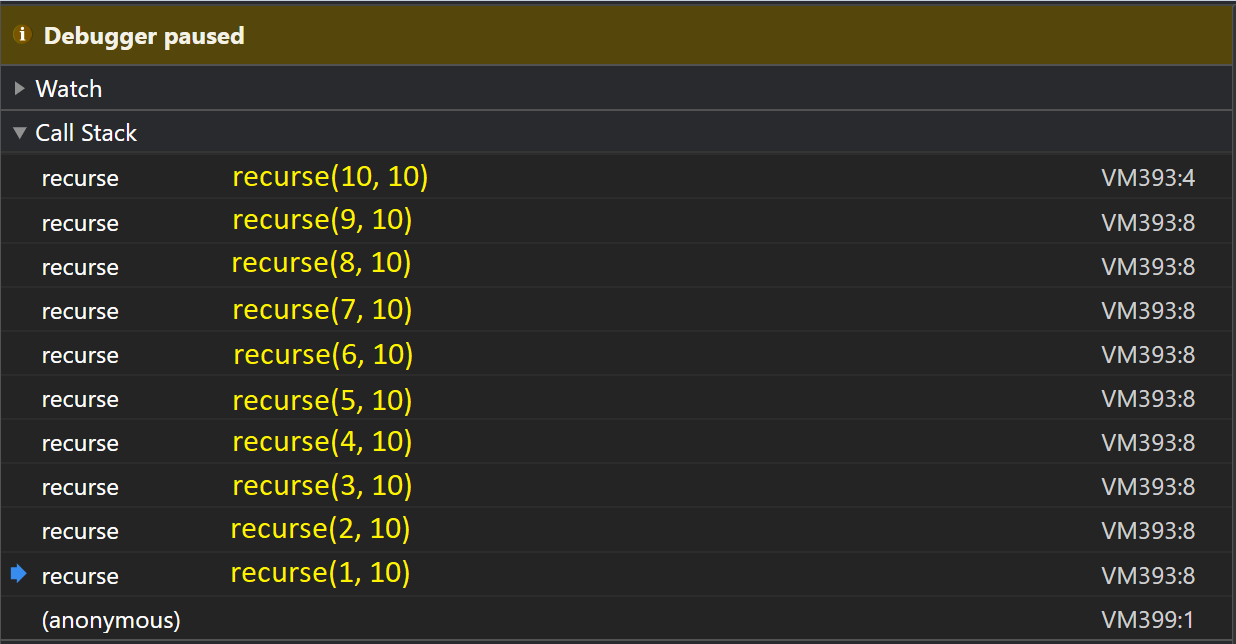

recurse(1, 10);

// 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10This code snippet will count from the start argument to the end argument. And it does so by calling its own function again.

So the order of this will look something like this:

Add a debugger inside the if blocks to follow this if it doesn't make sense to you. Recursion is one tool you can use to iterate in functional programming.

What makes the first example and the second example different? The second one has what we call "a base case". A base case lets the function eventually stop calling into itself infinitely. When start is equal to end we can stop recursing. As we know we have counted to the very end of our loop.

But each call of the functions is calling into its own function again, and adding on to the function argument.

The code example I just included for the counting example isn't a pure function. Why is that?

Because the console is state! And we logged string's to it.

This has been a brief introduction to recursion, but feel free to go here to learn more here.

Why use recursion?

Recursion allows us to stop mutating state variables, for one.

There are also certain data structures (tree structures) that are more efficient when solved with recursion. They generally require less code, so some coders like the readability of recursion.

Currying in Functional Programming

Currying is another tool used heavily in functional code. The arity of a function refers to how many arguments it receives.

// Let's talk arity

function arity2(arg1, arg2){} // Function has an arity of 2

function arity0(){} // Function has an arity of 0

function arity2(arg1, arg2, arg3, arg4){} // Function has an arity of 4

Currying a function turns a function that has an arity of more than 1, to 1. It does this by returning an inner function to take the next argument. Here's an example:

function add(firstNum, secondNum){

return firstNum + secondNum;

}

// Lets curry this function

function curryAdd(firstNum){

return function(secondNum){

return firstNum + secondNum;

}

}

Essentially, it restructures a function so it takes one argument, but it then returns another function to take the next argument, as many times as it needs to.

Why use currying?

The big benefit of currying is when you need to re-use the same function multiple times but only change one (or fewer) of the parameters. So you can save the first function call, something like this:

function curryAdd(firstNum){

return function(secondNum){

return firstNum + secondNum;

}

}

let add10 = curryAdd(10);

add10(2); // Returns 12

let add20 = curryAdd(20);

add20(2); // Returns 22Currying can also make your code easier to refactor. You don't have to change multiple places where you are passing in the wrong function arguments – just the one place, where you bound the first function call to the wrong argument.

It's also helpful if you can't supply all the arguments to a function at one time. You can just return the first function to call the inner function when you have all the arguments later.

Partial application in Functional Programming

Similarly, partial application means that you apply a few arguments to a function at a time and return another function that is applied to more arguments. Here's the best example I found from the MDN docs:

const module = {

height: 42,

getComputedHeight: function(height) {

return this.height + height;

}

};

const unboundGetComputedHeight = module.getComputedHeight;

console.log(unboundGetComputedHeight(32)); // The function gets invoked at the global scope

// outputs: NaN

// Outputs NaN as this.height is undefined (on scope of window) so does

// undefined + 32 which returns NaN

const boundGetComputedHeight = unboundGetComputedHeight.bind(module);

console.log(boundGetComputedHeight(32));

// expected output: 74bind is the best example of a partial application. Why?

Because we return an inner function that gets assigned to boundGetComputedHeight that gets called, with the this scope correctly set up and a new argument passed in later. We didn't assign all the arguments at once, but instead we returned a function to accept the rest of the arguments.

Why use partial application?

You can use partial application whenever you can't pass all your arguments at once, but can return functions from higher order functions to deal with the rest of the arguments.

Function composition in Functional Programming

The final topic that I think is fundamental to functional code is function composition.

Function composition allows us to take two or more functions and turn them into one function that does exactly what the two functions (or more) do.

// If we have these two functions

function add10(num) {

return num + 10;

}

function add100(num) {

return num + 100;

}

// We can compose these two down to =>

function composed(num){

return add10(add100(num));

}

composed(1) // Returns 111You can take this further and create functions to compose any number of multiple arity functions together if you need that for your use case.

Why use function composition?

Composition allows you to structure your code out of re-usable functions, to stop repeating yourself. You can start to treat functions like small building blocks you can combine together to achieve a more complicated output.

These then become the "units" or the computation power in your programs. They're lots of small functions that work generically, all composed into larger functions to do the "real" work.

It's a powerful way of architecting your code, and keeps you from creating huge functions copied and pasted with tiny differences between them.

It can also help you test when your code is not tightly coupled. And it makes your code more reusable. You can just change the composition of your functions or add more tiny functions into the composition, rather than having all the code copied and pasted all over the codebase (for when you need it to do something similar but not quite the same as another function).

The example below is made trivial to help you understand, but I hope you see the power of function composition.

/// So here's an example where we have to copy and paste it

function add50(num) {

return num + 50;

}

// Ok. Now we need to add 30. But we still ALSO need elsewhere to add 50 still

// So we need a new function

function add30(num){

return num + 30;

}

// Ugh, business change again

function add20(num){

return num + 20;

}

// Everytime we need to change the function ever so slightly. We need a new function

//Let's use composition

// Our small, reusable pure function

function add10(num){

return num + 10;

}

function add50Composed(num){

return add10(add10(add10(add10(addNum(num)))));

}

function add30Composed(num){

return add10(add10(add10(num)));

}

function add20Composed(num){

return add10(add10(num));

}Do you see how we composed new functions out of smaller, pure functions?

Conclusion

This article covered a lot. But I hope it has explained functional code simply, along with some of the repeating patterns you will see over and over again, in functional and even non-functional code.

Functional code isn't necessarily the best, and neither is object orientated code. Functional code is generally used for more math-based problems like data analysis. It's also very useful for high-availability real-time systems, like stuff written in Erlang (a functional language). But it genuinely does depend problem to problem.

I post my articles on Twitter. If you enjoyed this article you can read more there.

How to learn more

Start here, with freeCodeCamp's introduction to functional programming with JavaScript.

Look here for some libraries you can include and play around with, to really master functional programming.

Peruse this good overview of lots of functional concepts.

Finally, here's an excellent jargon-busting glossary of functional terms.